The death of Jah’Nae Campbell underscores the lax oversight of Philadelphia’s low-income rental housing | Editorial

As repeated complaints went unheeded, the 12-year-old's family blames substandard living conditions inside their West Philly affordable housing complex for her death.

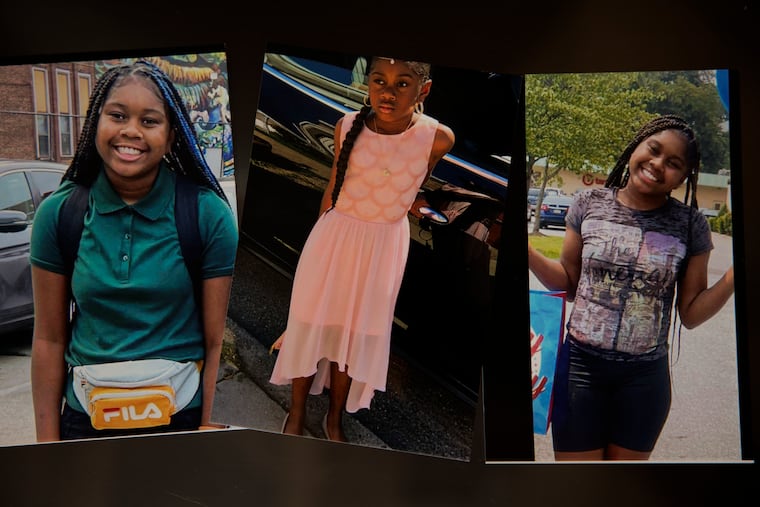

Did 12-year-old Jah’Nae Campbell die because of where she lived?

The courts will get to decide whether the nonprofit landlord, HELP USA, and its property manager are liable for her death. But what is clear is that the West Philadelphia apartment she shared with her mother and siblings had a myriad of housing code violations — from a broken ceiling to mold climbing the walls — and that no one in charge did much to help, regardless of years of complaints.

As reported by The Inquirer’s Ryan W. Briggs and Samantha Melamed, the toxic conditions in the apartment worsened Jah’Nae’s asthma, which afflicts Philadelphians at three times the national average. On March 8, Essie Campbell rushed her daughter to Penn Presbyterian Medical Center because she couldn’t breathe. According to doctors, the young girl’s heart stopped.

Jah’Nae’s story is unbearably sad, but while the family was alone in their struggle to improve their living conditions, their situation is far from an aberration. Philadelphia has one of the oldest housing stocks in the nation, leaving many of the city’s poorest residents forced into housing in substandard and sometimes dangerous situations.

According to a 2021 study by the Pew Charitable Trusts, roughly 30% of the city’s rental units lack a rental license entirely, and only 7% of the city’s rental units are inspected during a given year. This presents a troubling lack of clarity on how many households are renting units that fail to meet basic habitation standards.

In Jah’Nae’s case, despite multiple requests from her mother and doctors, the family’s landlord failed to remediate the hazards they lived with. Meanwhile, the city’s Department of Licenses and Inspections also failed to protect Jah’Nae and her family.

Although the city does not inspect units before issuing a rental license, it does perform inspections upon receiving a complaint. Campbell filed several complaints, but no city inspectors entered her home or issued violations for the appalling conditions inside.

While L&I has cited a lack of access to the property as a reason for its lack of action, it is also possible that longtime dysfunction within the department played a role. In recent years, high turnover among building inspectors and other employees has posed a challenge to the department’s code enforcement efforts. The reasons cited for leaving L&I by departing workers include overwork, mismanagement, and political interference in the inspection process.

The city must address that dysfunction as it seeks to hire more inspectors. L&I could potentially use outside contractors to ensure more rentals are habitable and registered.

Another way to ensure better conditions in the city’s older rentals lies in billions of federal dollars set aside in the Inflation Reduction Act. While federal housing incentives have long left renters behind, the Inflation Reduction Act contains several programs specifically designated for multifamily housing, often targeted toward older buildings that tend to offer more affordable housing options.

Given federal rules around how area median income is calculated, most of the older rental stock in Philadelphia is likely eligible.

Leaning into these initiatives would be a strong fit for Mayor Cherelle L. Parker, who as a member of City Council championed programs like Basic Systems Repair and Restore Repair Renew, which targeted low- and moderate-income homeowners. The federal money gives the mayor the chance to bring similar benefits to people in rental housing, a growing and disproportionately cost-burdened part of our city.

Unless Philadelphia is planning to add tens of thousands of housing choice vouchers or build an unprecedented amount of new deeply affordable housing, the poorest renters will remain in the kind of older and decaying apartments that trap families like Jah’Nae Campbell’s.