Dick Allen has captivated Philadelphia for 60 years. Will his legend finally reach the Hall of Fame?

Allen’s career is like a legend filled with stories that seem to grow with time, including an unlikely home run contest in 1987.

Dick Allen was nervous.

He captured Philadelphia’s imagination with a 40-ounce bat and Herculean swings that made baseballs look like golf balls as they soared out of Connie Mack Stadium. He was the man, a favorite for a generation of fans who fell in love with the Phillies listening on transistor radios after bedtime.

But that was 20 some years earlier. Allen was 45 and a decade removed from his final big-league homer.

The Phillies invited him in the summer of 1987 for a home run contest, a promotion between games of a doubleheader at a packed Veterans Stadium. The fans wanted to see Crash, the star they loved so much as kids in the 1960s that they refused to leave a game early if Allen was due up again. Forget how long it had been since Allen last played. They wanted one more majestic home run.

» READ MORE: Former Phillies star Dick Allen is getting a mural thanks to the mayor and the ‘Secretary of Defense’

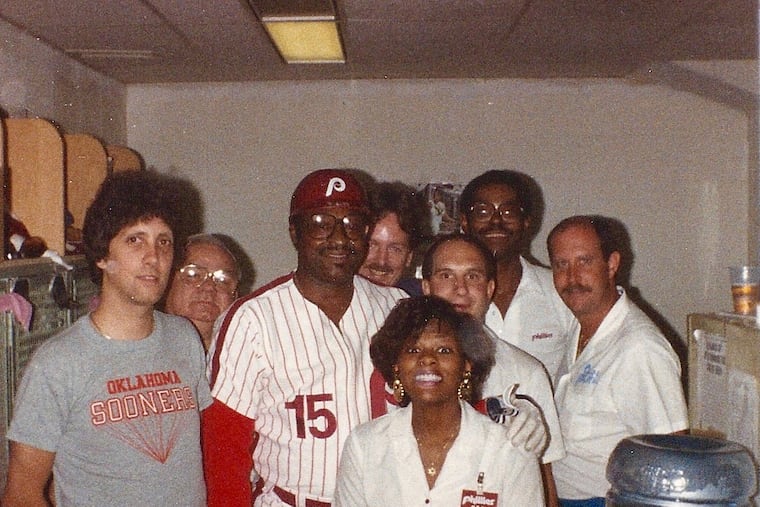

Allen rarely swung a bat in retirement, spending time instead on his horse farm. So Allen did not practice for the contest, which pitted him against Greg Luzinski in a “Bull Blast.” Allen tugged on his old No. 15 jersey and went to the grounds crew office.

It was there — a small room in the bowels of the stadium where Allen hung as a player — where Allen could ditch his cape and be himself. The Vet’s grounds crew was a bunch of South Philly guys who started at the stadium as teenagers. They turned their cinder-block office into a lounge with a sofa and toaster oven, creating a gathering spot for players looking to hide from the press before a game. Allen was always welcome.

The grounds crew worshiped Allen as kids. They sat in the 50-cent seats at Connie Mack Stadium and waited for Allen to hit one over the Coca-Cola sign atop the roof in left-center field. But the guys manicuring the Vet’s dirt eventually grew to see the larger-than-life figure who walked to the plate to “Jesus Christ Superstar” as the regular guy Allen wanted to be. They clicked.

The Vet crowd that night was buzzing to see the Allen they remembered. But the aging star told his buddies in the lounge that he wasn’t sure he could do it. Even superheroes get old.

“He didn’t want to embarrass himself,” Mike DiMuzio said. “Here’s this guy who everybody thought was the best home run hitter that the Phillies ever had and now is he going to be able to hit home runs? The first hour of his night was spent with us quote-unquote little guys. So to say Dick went out with Gatorade on his breath was probably a lie, but he did have some liquid before he got in there. He just didn’t want to embarrass himself.”

A case for Cooperstown

What makes a Hall of Famer?

There are 346 plaques in Cooperstown, N.Y., honoring the game’s greats. They were the ones whose cards you stopped to inspect when ripping through a pack, the ones whose batting stance you copied in the yard, and the ones you circled on the pocket schedule so you didn’t miss them coming through town. They were different.

Allen’s case will be dissected Sunday for the third time in 10 years when a 16-person committee meets in Dallas. He needs to receive 12 votes from the Classic Era Committee to become a Hall of Famer. Allen, who died in 2020, fell one vote shy in each of his previous two chances with that committee.

» READ MORE: Dick Allen, the Phillies’ first Black star, didn’t let the boos and racism stop him from becoming an icon

He did not hit 500 home runs or record 3,000 hits. He never won a World Series, didn’t love the press, and clashed with managers. But Allen made seven All-Star teams, was the NL Rookie of the Year, and won an MVP award. His 165 OPS+ from 1964-73 — Allen’s prime — leads all players. He was one of the best hitters of his generation as his 319 homers and 975 RBIs from 1964-74 trail only Hall of Famers.

Allen has the numbers to fit into that room in Cooperstown. But it takes more than numbers to make it. You have to be special. And that’s how Allen has long been seen in Philadelphia. Sixty years ago, he grabbed hold of a generation and never let go.

He hit homers over the roof with a baseball bat that looked like a wagon tongue. He told his teammates he would hit three homers in a game and then did it. He talked to the fans by writing messages in the dirt. His career is like a legend filled with stories that seem to grow with time.

“When he hit ground balls, you would hear the crack of the bat and then see a poof of dirt in the infield,” said Chris Wheeler, the former Phils broadcaster who idolized Allen at Connie Mack Stadium before working for the team. “Nowadays they talk about exit velocity, well you knew that was hit hard because the fielder could barely react. Poof. It was right through the infield.”

The Phillies went 59-95 in 1960, the year they signed Richard Anthony Allen from a tiny Western Pennsylvania town named Wampum. Baseball was still king in Philadelphia, but the Phillies were terrible and the A’s were gone. The Whiz Kids were ancient history. Young Philadelphians were desperate for a star.

Allen was the Rookie of the Year in 1964, the season the Phillies blew a trip to the World Series. That September still stings. But that summer was glorious. It delivered a star ballplayer to a generation. The legend of Allen was already growing.

“I know it’s a romantic thing from my childhood, but there are still things to this day that he did that no one else did,” said Dennis Durkin, who grew up in Northeast Philly and has a shrine to Allen at his home in Tennessee. “I’ve never heard the ball get hit and sound like that. He hit the ball so hard and it had a different sound to it. He’s the only real sports hero I ever had. It was a pure love that only a child can have. I’m 71 years old and I still have that in my heart for me.”

He averaged nearly 30 homers a season in his first six full seasons in Philadelphia before writing in the dirt his wishes to be traded after the 1969 season. Allen’s Philadelphia story was never the same after he fought Frank Thomas, a white teammate who had been needling him, during batting practice in 1965.

» READ MORE: Chase Utley’s iconic walk-up song can be traced back to Dick Allen and a White Sox organist

“He had no chance in Philadelphia in 1965 with a Black guy hitting a white guy,” Wheeler said. “It didn’t play. It just didn’t play. He was done after that. It was basically over. And I think that’s one of the marks that he carried.”

The kids who marveled at Allen’s home runs were old enough to be baseball fans but young enough to be ignorant to the city’s social climate that chased Allen out of town. Allen was their hero, a ballplayer they spoke of as if he came off the pages of a tall tale. Nothing else mattered.

“As a child, I couldn’t understand why anyone would bother him,” Durkin said. “This guy was like a Greek god. I’m going, ‘This guy is the greatest thing that ever happened.’ And only a child could see it that way. Never, ever, ever crossed my mind. We were just there.”

A perfect ballpark

The traffic usually backed up on Lehigh Avenue, making it easier to get off the bus a few blocks early and walk toward Connie Mack Stadium. You just had to follow the light towers that hovered over the North Philadelphia rowhouses, a beacon that the ballpark was near.

There was the Ballantine scoreboard, the pristine infield, and the red seats that cost just 50 cents. It was the perfect place to fall in love with baseball.

“It was the greatest,” DiMuzio said. “And then you get the smell of the grass and the popcorn and all that.”

DiMuzio spent his Sundays at the ballpark, buying a ticket upstairs knowing that he would finish his day near the front row.

“When Dick Allen came to bat, you didn’t move,” DiMuzio said. “You didn’t get up. You wanted to see how far he could hit a ball. You weren’t leaving early. I never left early. You wanted to see what would happen. He hit some majestic shots and you just wondered how a guy could do that.”

So imagine how DiMuzio felt when he started as a junior groundskeeper in 1971 at Veterans Stadium. A senior at Bishop Neumann High School, DiMuzio watched as Allen walked into the groundskeeper’s office at the Vet. Allen, in town with the Dodgers, wanted to see his old buddies from Connie Mack Stadium.

» READ MORE: Filmmaker Mike Tollin revived SlamBall. Now he hopes to make movies about Dick Allen and Jon Dorenbos.

“It was amazing,” DiMuzio said. “And then after the game, he stopped back to get a beer. That’s what he would do. He would come into the room and hang out. It was like, ‘Who are these guys to know me?’ I’m just some kid from South Philly and this guy wants to hang out with me? When I first started as a 17-year-old, everything was larger than life. Then I got to learn that these guys are just everyday, normal guys. It was unbelievable that someone with his stature would even think to say, ‘Hey, Mike. How are you doing?’”

Allen had a farm in Perkasie where he raised horses. He loved going to the track, famously missing a doubleheader because he was at Monmouth Park instead of Shea Stadium. He wore cowboy boots and often said he should’ve been a farmer. Maybe that’s why Allen hung with the groundskeepers.

The office was always his first stop when he came in as a visiting player and he even flew to Philadelphia to be a pallbearer when one of the groundskeepers was killed. The superstar ballplayer fit in with the guys who always had their hands in the dirt.

“That’s 100% who he is,” said his son Richard. “Grounded. He’s just a grounded type of guy. You would literally see him at the racetrack sleeping in bunk houses. He just wasn’t one for the starch cloths and chandeliers. He felt comfortable around people who he felt were real. They weren’t putting on an image to him, and he wasn’t going to put on an image to someone else.”

‘Let’s go get a cold beer’

Allen returned to Philadelphia in 1975, joining a Phillies team on the cusp of contention. It had been five seasons since Allen played for the Phillies and his exit was not smooth. He wondered how the fans would treat him. It didn’t take long to see that the love from the 1960s was still there.

The crowd gave him three standing ovations in his first game at the Vet, cheering so loudly that Larry Bowa said he had chills. So Allen knew in 1987 as he toasted his buddies on the grounds crew that the fans were ready to roar. But could he deliver?

“He’s 45 years old and hasn’t swung a bat in I don’t know how long,” DiMuzio said. “He’s been with his horses for years. He’s not a guy who will spend three hours in a batting cage prepping for a home run derby. He just said, ‘I’ll go out and I’ll swing. If it goes over, it goes over.’”

» READ MORE: Chase Utley, Jason Kelce and 8 other Philly athletes who could make the Hall of Fame

He took a couple swings in the tunnel, headed to home plate, and made the Vet feel like Connie Mack Stadium.

“I was mesmerized by it,” Wheeler said. “Anyone who saw it will tell you it was the greatest show they’ve ever seen. One after another, they were hitting them out. Those two were launching them that night. It was scary what they did. Oh my God. I’ll never forget that.”

The Phillies and Dodgers players were on the top step of their dugouts watching the show. The two sluggers could still slug. Richard was in the outfield, shagging fly balls as Luzinski and Allen took their swings.

“I felt like I was in the infield with some of the balls that were hit out there,” Richard said. “They were smoked. For me, it gave me goose bumps.”

Allen hit seven homers and lost by one to Luzinski, who was eight years younger. Allen was gassed by the end, Richard said. They agreed to do it again the next summer. Allen didn’t need any practice. He could still marvel. The legend of Dick Allen continued to grow that night.

The grounds crew office was like his phone booth. He stepped inside and became super again.

“He didn’t embarrass himself,” DiMuzio said. “He was fine with that. It was, ‘Let’s go get a cold beer.’ He was my idol.”